“The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.”

– William Shakespeare, As You Like It, Act 5, Scene 1

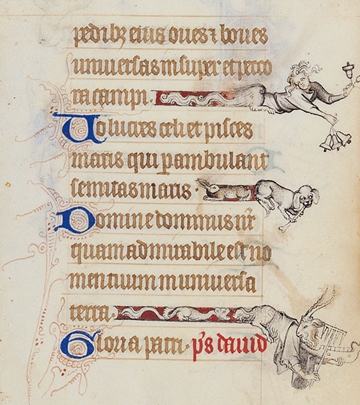

The fool was not invented in sixteenth-century England, but many of the characteristics we associate with the type were crystallized at that moment.

Artists, writers, kings and noblemen found good use for the fool, holding him up as both an oddity and an oracle.

Today we might understand fools as a cross between circus clowns and late-night comedians—they make us laugh, mainly by making us see how foolish we are.

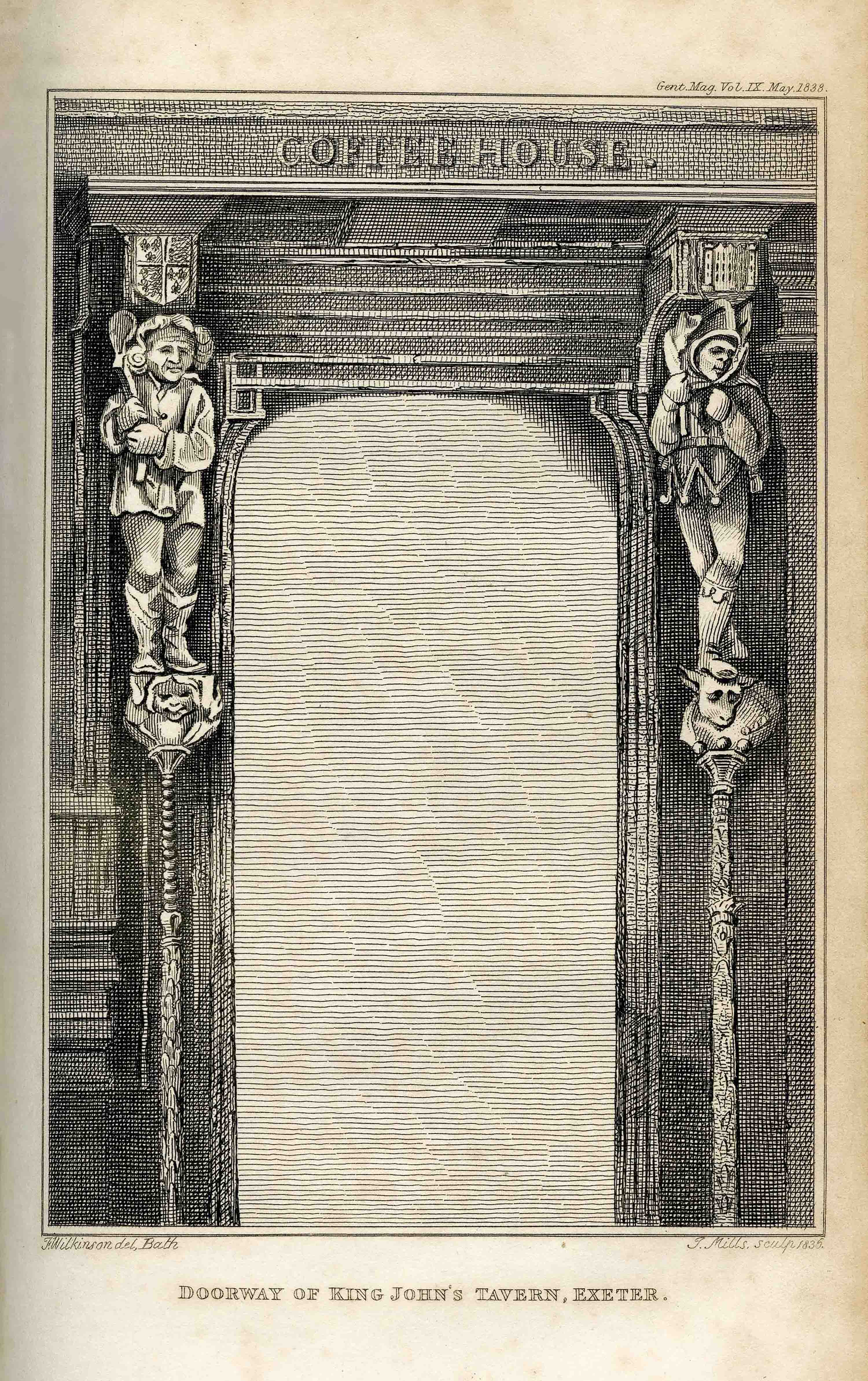

See the jester and other sculptures from Henry Hamlyn’s home at The Met Cloisters.

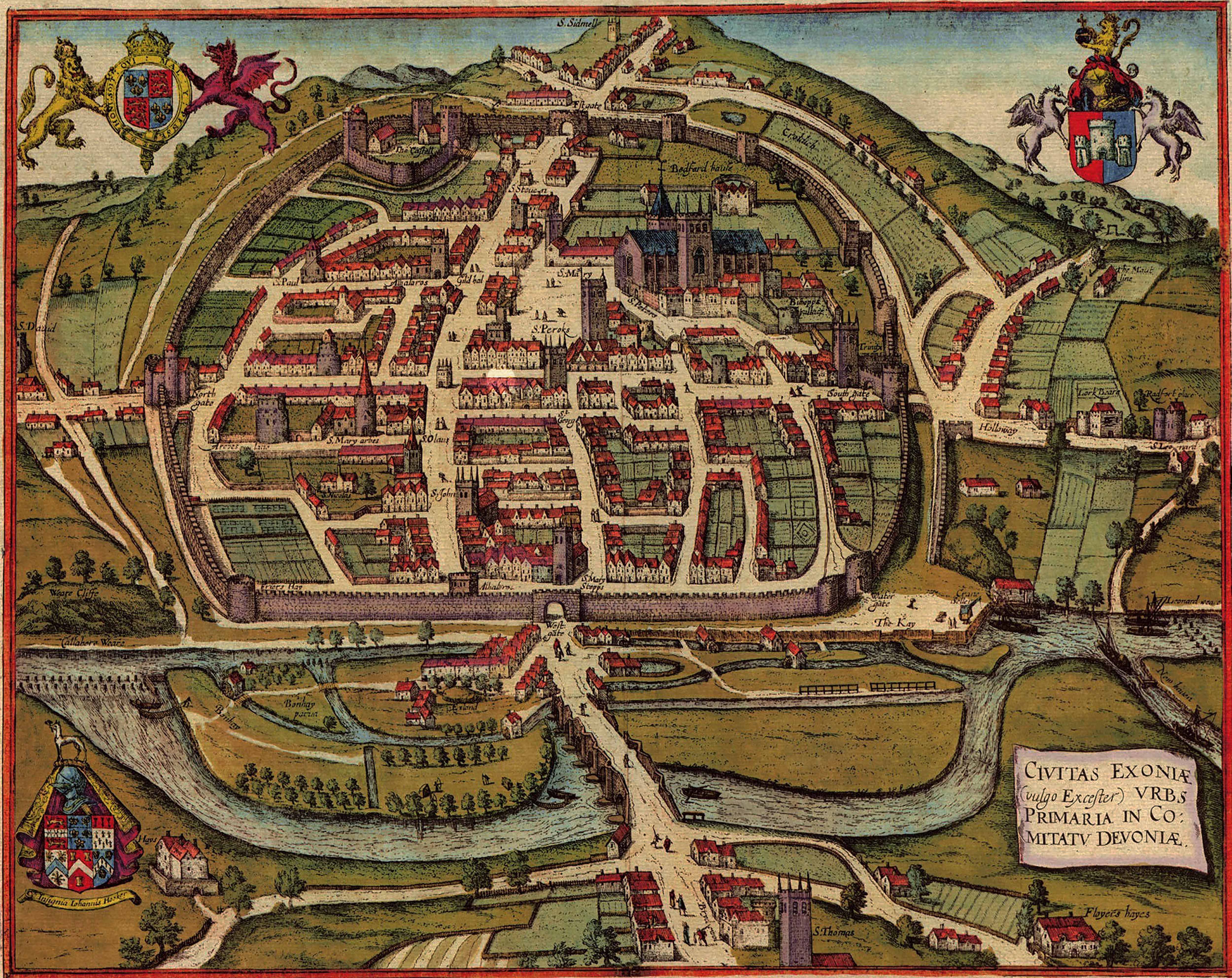

Rich Man, Poor Man: Art, Class, and Commerce in a Late Medieval Town is now on view.

Credits

Architectural Support with a Jester, 1524–1549. French, Made in Exeter, England, by French woodworkers. Oak, 83 x 9 1/2 x 9 1/4 in., 101 lb. (211 x 24.1 x 23.5 cm, 45.8 kg). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1974 (1974.295.1)

Watercolor by Edward Ashworth (English, 1814–1896). King John Tavern (formerly the home of Henry Hamlyn), 1830–40. The Devon and Exeter Institution

Hans Schäufelein (German, ca. 1480–ca. 1540). Musicians and Onlookers. Woodcut, 10 3/4 x 16 in. (27.3 x 40.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Harry G. Friedman, 1949 (49.120)

Etching by Georg Braun (German, 1541–1622) and Frans Hogenberg (Flemish and German, 1535–1590). Map of Exeter from Cities of the World, 1617. Alamy Stock Photo